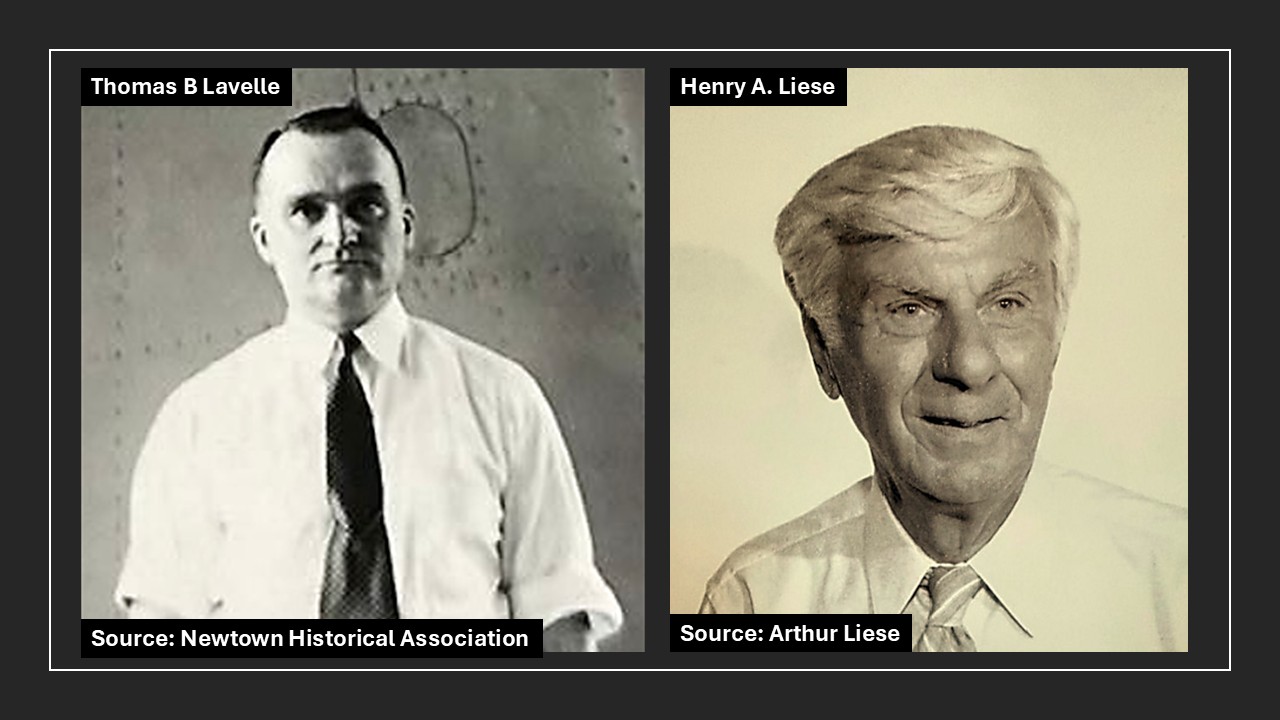

Lavelle was co-founded by Thomas B. Lavelle, a sheet metal fabricating specialist and project manager, and Henry A. Liese, a mechanical engineer, in December 1941. Both had extensive experience in the aircraft manufacturing industry, beginning with the famous Loening Aeronautical and Engineering Company on Long Island, NY, and then with Carl de Ganahl, engineer and founding owner of Fleetwings, Inc.

Fleetwings was the first manufacturer of stainless steel components and amphibious aircraft which had relocated from Roosevelt Field, Long Island to Bristol, Bucks County, PA after purchasing the factory site previously owned by Keystone Aircraft, located on the Delaware River, in 1934.

Lavelle and Liese were able to secure a major portion of their initial start-up capital for the founding of the Lavelle Aircraft Corporation through a large stock contribution from their first Long Island employer, Grover Loening.

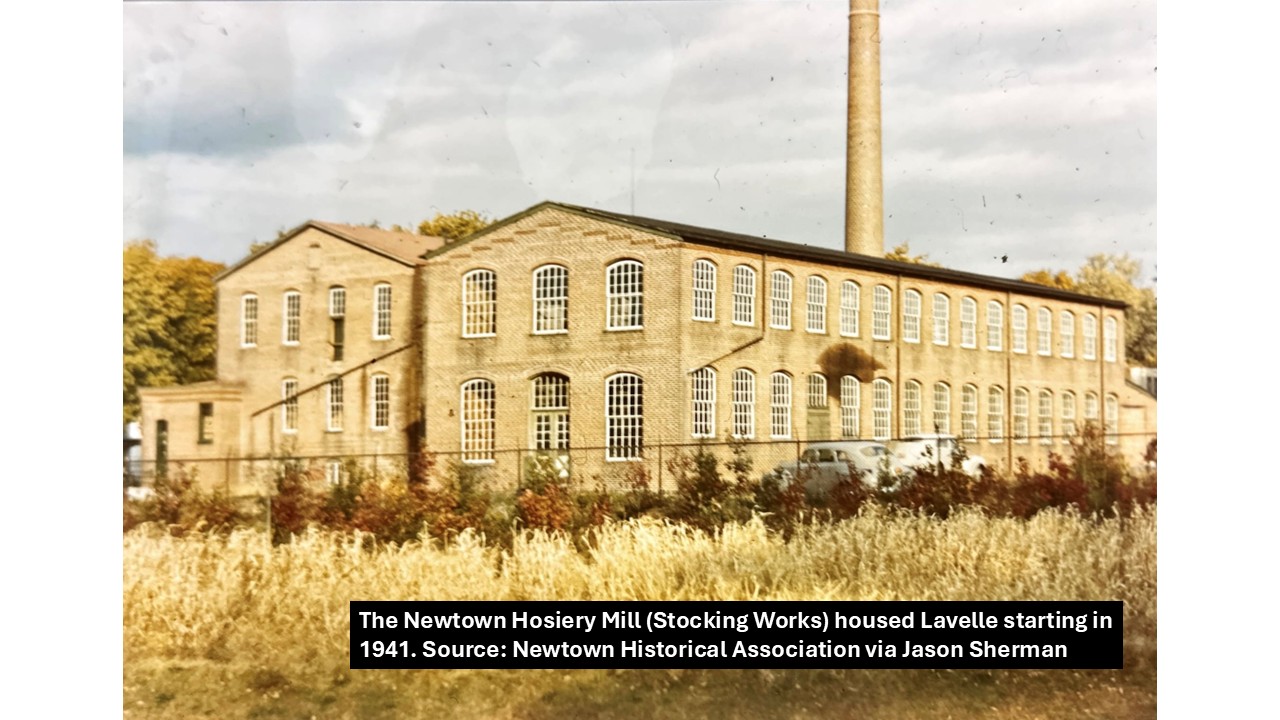

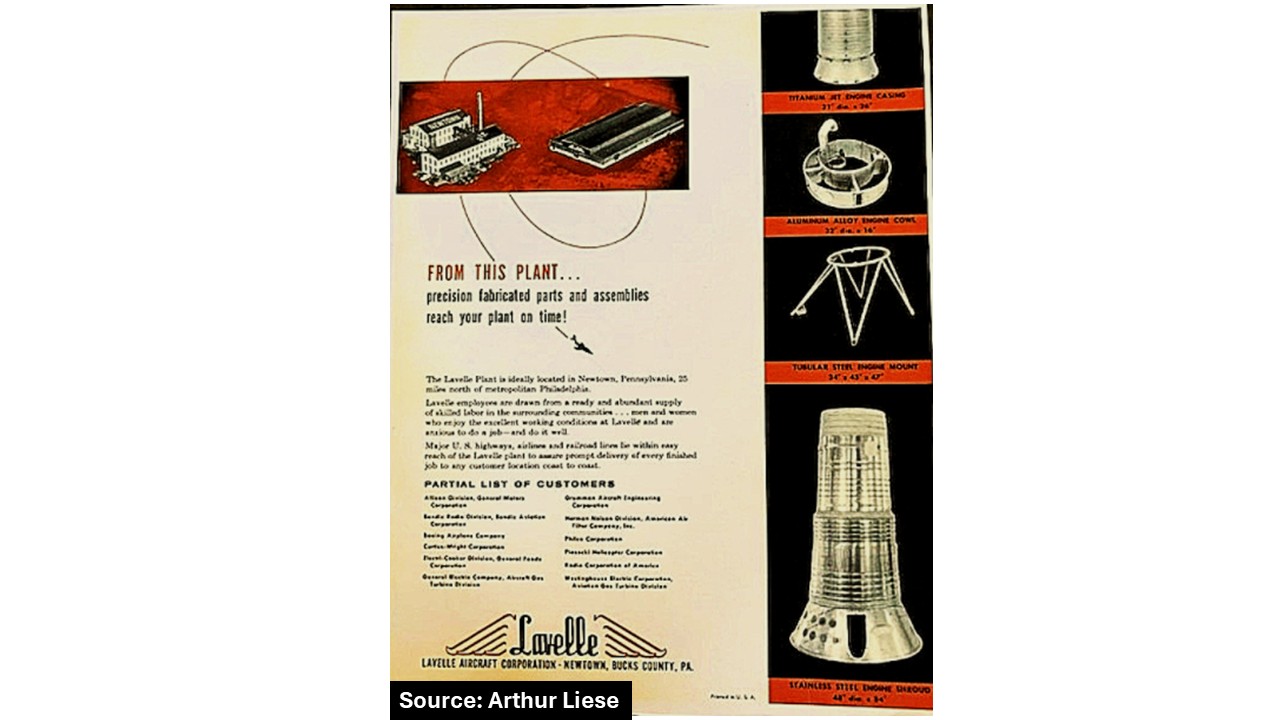

Lavelle was primarily located in a building which had formerly housed the Newtown Hosiery Mill (aka Stocking Works). Eventually, Lavelle expanded its footprint to include an adjacent building which had housed the Newtown Tile Company and another building in Newtown which had been owned by George Stockberger, a local Chevrolet automobile dealer. Eventually, Lavelle also rented storage space in a dairy barn in Wrightstown, PA!

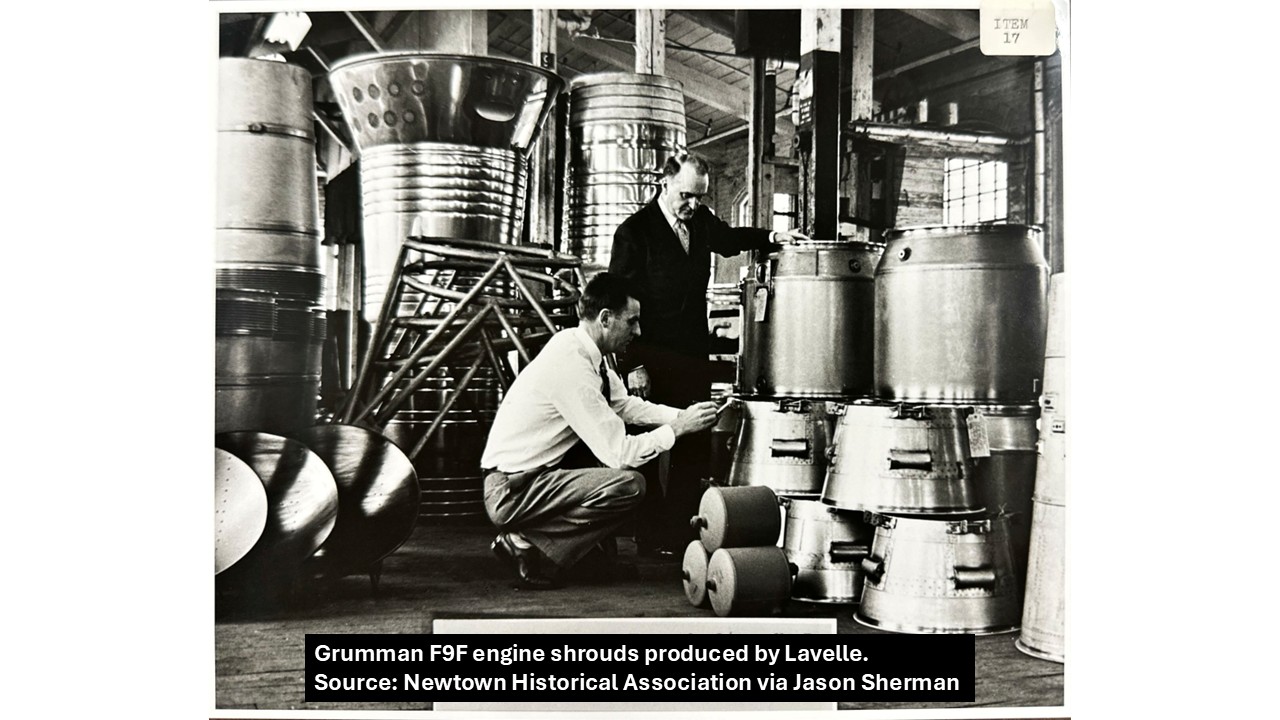

Many sheet metal craftsmen, machinists, tool and die makers, and welders came to work for Lavelle Aircraft to escape the unionization of Fleetwings, Inc., which had been acquired by Henry J. Kaiser Industries. It did not take long for Lavelle to develop a reputation as a quality fabricator of precision stainless steel sheet metal aircraft parts as well as machined stainless steel components. It also became a principal subcontractor to Grumman Aircraft and Engineering Corporation of Bethpage, Long Island. Lavelle manufactured stainless steel sheet metal sub-assemblies and components for every Grumman Navy fighter, beginning with F4F Wildcat, F6F Hellcat, F-7 Tigercat, TBF Avenger, F9F Cougar (the first Navy jet fighter in the United States), F9F Panther up to and including the F14 Tomcat. Additional Grumman aircraft Lavelle provided components for included the S2-F (series), A6A Intruder, E6B Tiger, 0V-1 Mohawk, and E2C Hawkeye.

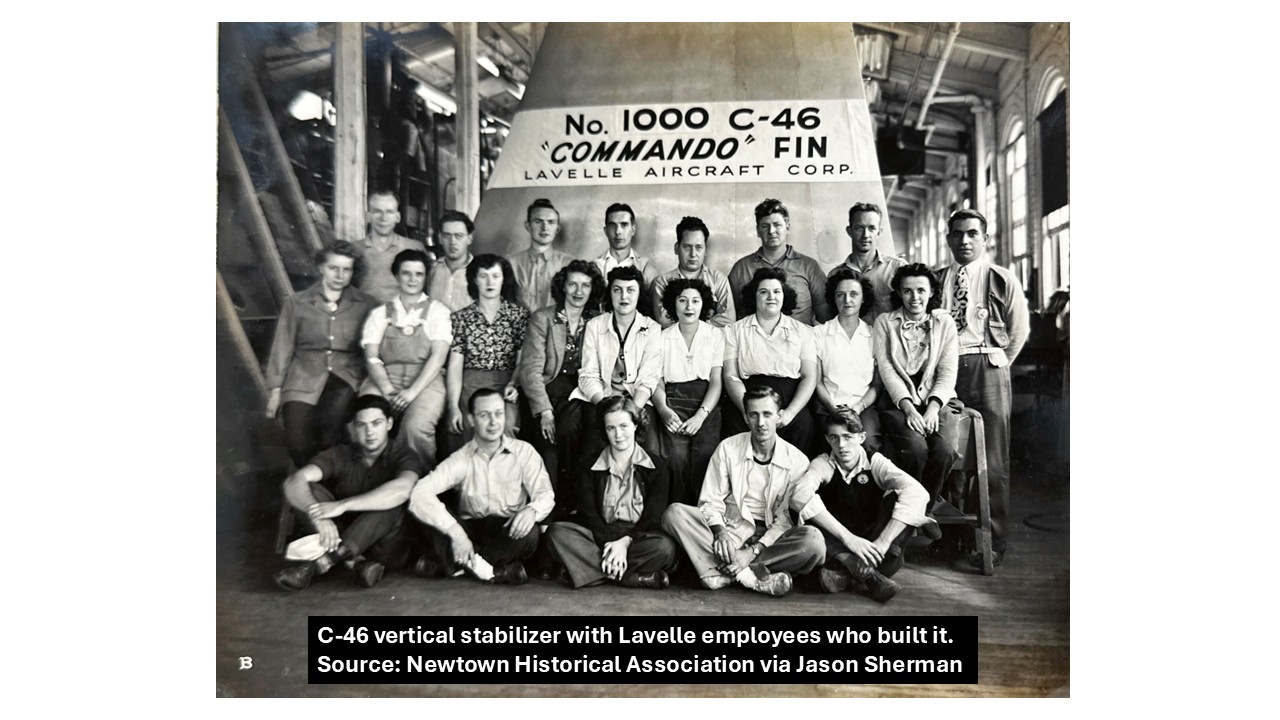

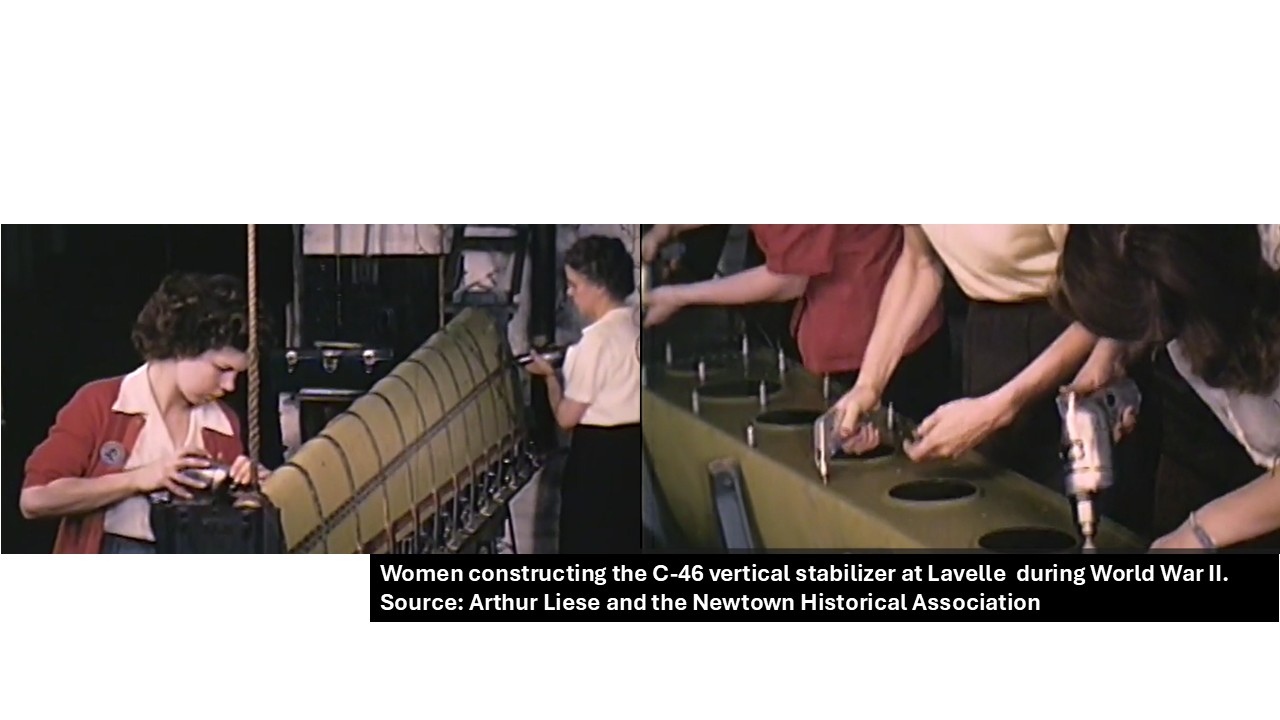

Lavelle was also subcontracted to produce parts for the Martin B-26 Marauder bomber, and engine cowlings, dorsal fin, ammunition boxes and rear gun mounts for the Navy's Brewster F2A Buffalo, a fighter-based torpedo bomber. Ammunition boxes, feed trays and wing fairings were also manufactured for the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk as well as the vertical stabilizer (fin) for the Curtiss C-46 Commando cargo plane.

During World War II, the company grew to 700 employees and was the largest employer in Newtown at the time. Lavelle had their own “Rosie the Riveters” during the war as well; due to the male labor shortage, local women were hired and trained by Henry Liese to rivet various sheet metal components; notably, for the entire production of the C-46 Curtiss Commando vertical stabilizer.

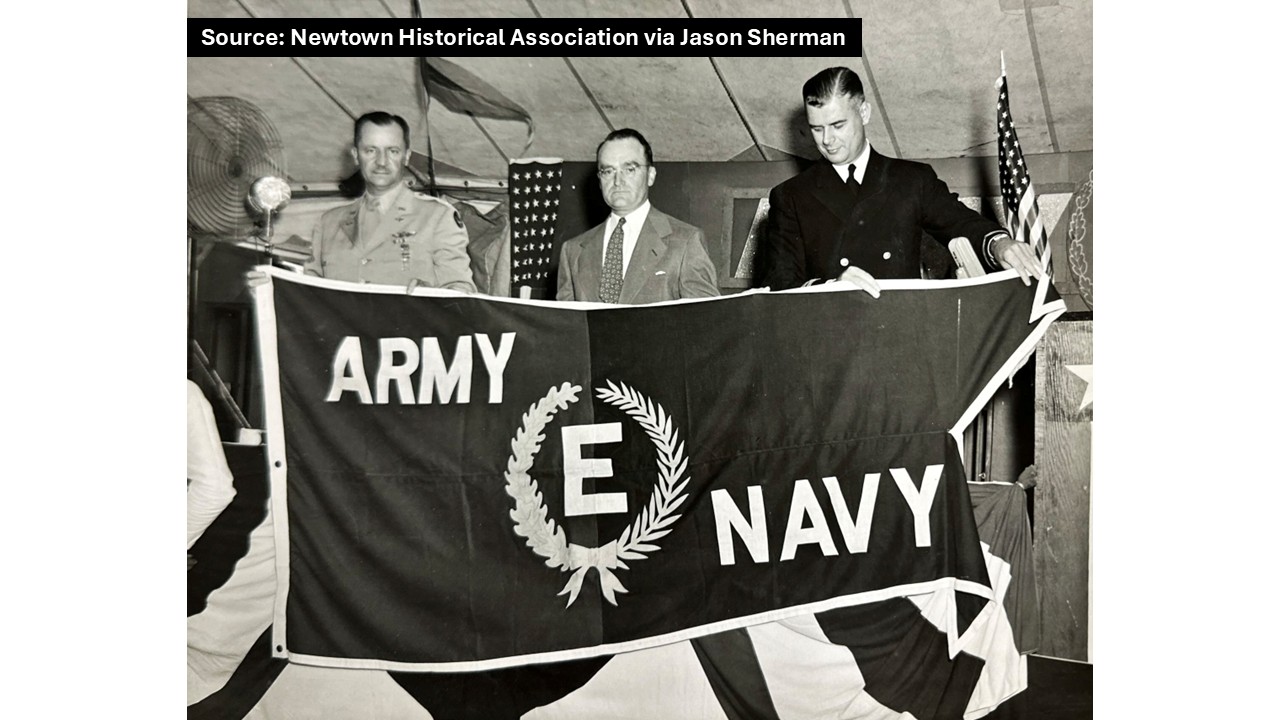

Lavelle was awarded multiple Navy and Army-Navy “E” Production Awards during World War II for their work. These “E” Awards were honors presented to companies and organizations during World War II whose production facilities achieved "Excellence in Production" ("E") for equipment for the war effort.

Once the war ended, government contracts for aircraft parts were cancelled or not renewed.

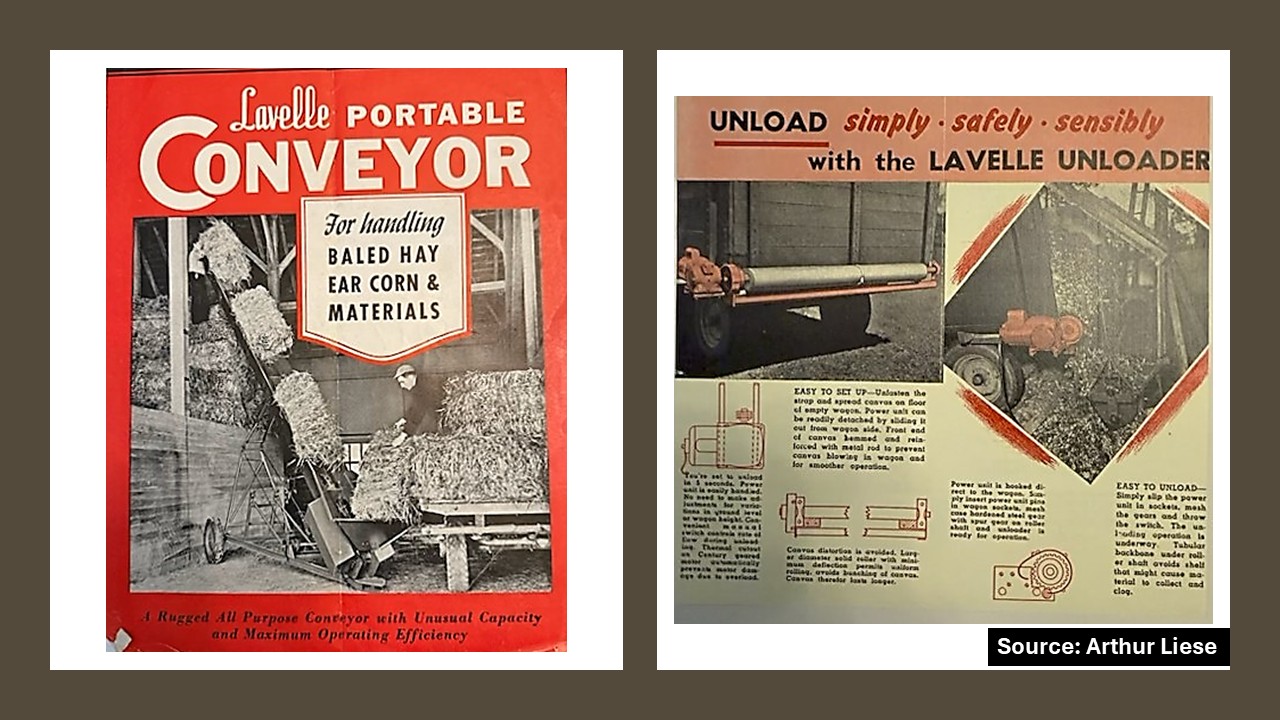

In order for Lavelle to survive, prosper, and most importantly, to retain its loyal employees, it looked to the surrounding farming community of Bucks County, PA for inspiration and developed and opened a Farm Division (1945-1953). The focal point of the Farm Division was to utilize aircraft engineering and materials as well as its sheet metal manufacturing expertise for designing, fabricating and marketing farming conveyors, grain elevators, unloaders and bolt-on replacement parts.

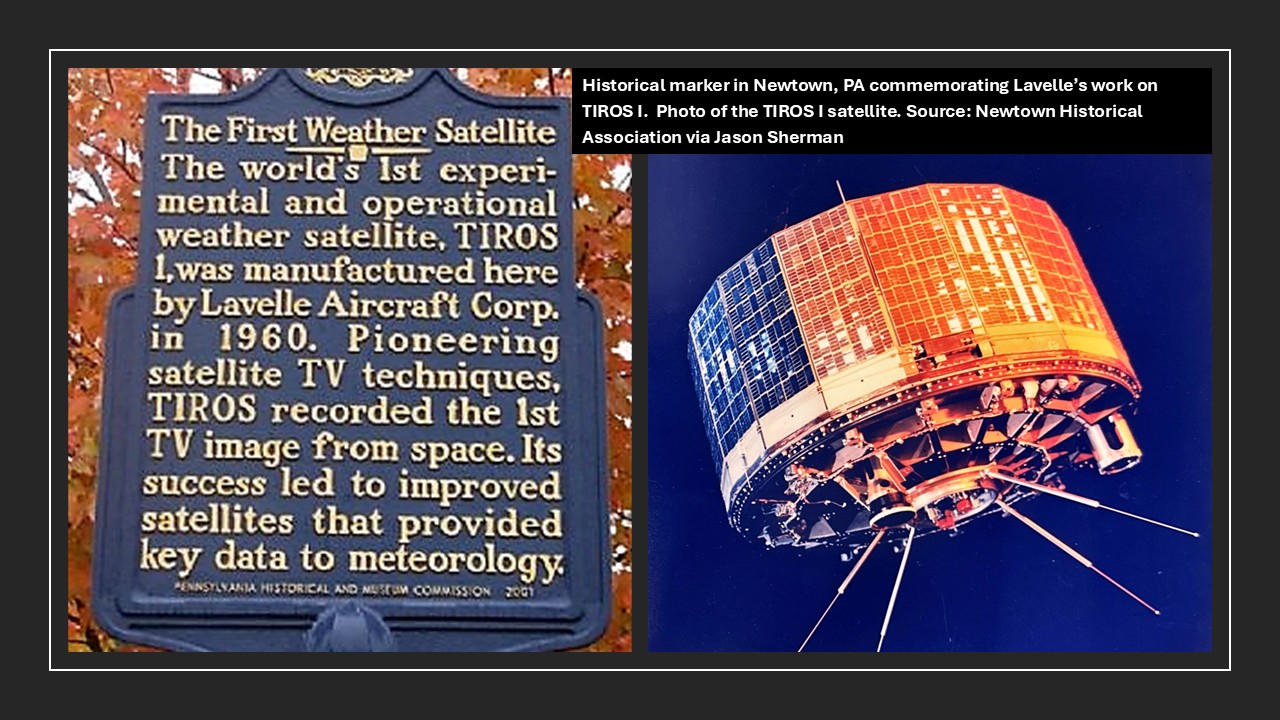

In 1957, RCA subcontracted Lavelle to build TIROS, the Television and Infra-Red Observation Satellite. While RCA had extensive experience in television technology, the company had virtually no knowledge of the fabrication of sheet metal manufactured parts.

Constructed of aluminum alloy and stainless steel, the eighteen-sided disk-shaped TIROS I was covered with 9,200 solar panels to power its camera and data-storage devices. Launched on April 1, 1960, TIROS I proved the feasibility of video observation of weather by satellites.

In the years that followed, Lavelle built six of the nine TIROS satellites, the Telstar communication satellite which NASA launched in 1962, and Ranger 7, which observed the moon in 1964.

Ranger 7 was the first space probe of the United States to successfully transmit close images of the lunar surface back to Earth. It was also the first completely successful flight of the Ranger program. Launched on July 28, 1964, Ranger 7 was designed to achieve a lunar-impact trajectory and to transmit high-resolution photographs of the lunar surface during the final minutes of flight up to impact. The images were used for selection of lunar landing sites during Project Apollo.

Grumman turned to its long-standing relationship with its reliable friend and subcontractor Lavelle once again to support its Apollo Lunar Module program. Lavelle built the antenna head yoke device for the lunar module. This was an important component of the rendezvous radar used on the spacecraft.

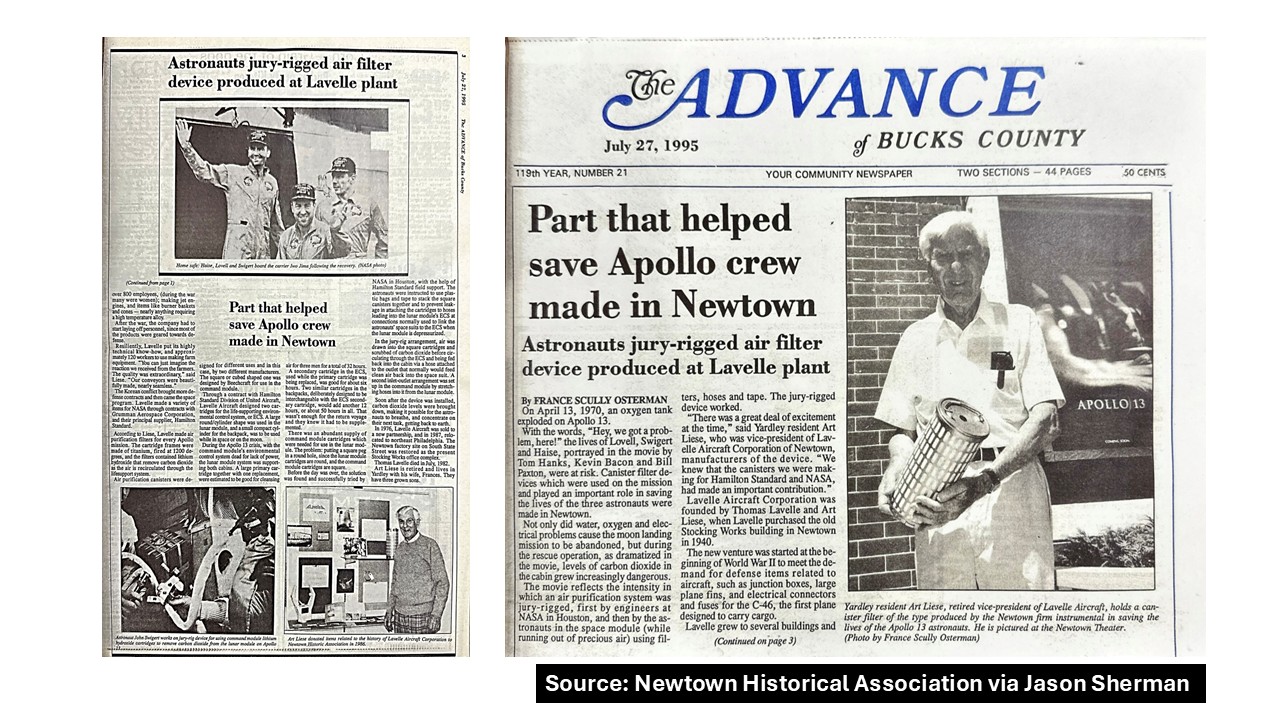

Lavelle also constructed lithium hydroxide canisters used in astronaut extravehicular activity (EVA) suits to remove exhaled carbon dioxide from the suit wearer. The canisters were the same ones used in the Lunar Module’s environmental control and life support system; Lavelle initially was the sole supplier of the canisters for NASA, but later became a co-manufacturer with Hamilton-Standard, who, along with Lavelle, pioneered and refined the design and development of the EVA suits worn by astronauts on the lunar surface.

Henry Liese’s son, Arthur, recounted the story of how Lavelle helped to solve the carbon dioxide build-up problem in the spacecraft during the Apollo 13 crisis by using the cylindrical lithium hydroxide canisters they manufactured:

“Virginia Perkins was the company switchboard operator [at Lavelle]. She took the initial call from NASA and referred it to Ed Oberndorfer (Obi’), the chief engineer at the time. Obi, in turn, called my father, and he went up to the engineering department to field the description of the problem from NASA. Dad then contacted Ed Schneck, a manager of the stockroom, to bring up a number of parts to the engineering department. (The stockroom contained hand tools and components used in the manufacturing process at Lavelle.) ‘Schecky’ took up all the [requested] equipment and materials to [Dad and Obi], including duct tape. Once these various components were in hand, my father and Obi began experimenting with how they were going to make the lithium hydroxide cylinder fit into the square Command Module carbon dioxide filter component. They devised a process to adapt the cylindrical cartridge to the square component with duct tape. And so, the duct tape was a key component because [the astronauts] had [that] in the spacecraft. In fact, Dad joked, ‘the whole world is held together by duct tape and not many people know it.’ By describing the simple process they developed [to NASA], the astronauts [in turn] were able to duplicate it in their spacecraft. Ironically, as you might guess, Hollywood gave NASA engineers full credit for this whole rescue operation. The duct tape was a key component because it made this whole [contraption] airtight.”

In 1976, Henry A. Liese and Thomas Lavelle sold their controlling interest in the Lavelle Aircraft Corporation. Unfortunately, unlike Lavelle and Liese, the new owner had limited military relationships from which he could continue to obtain contract work for the company. Sales dwindled, and Lavelle relocated to northeast Philadelphia in 1987 to take advantage of City of Philadelphia tax incentives, but sales continued to lag, resulting in another company sale in1988 and finally closure due to bankruptcy by 1999.

Arthur Liese oral history. Recorded by The Southeastern Pennsylvania Cold War Historical Society, June 19 and 26, 2025. (Unpublished.)

Arthur Liese conversation, August 28, 2025.

Liese, Arthur. Personal notes on Lavelle Aircraft Corporation, July 9, 2025. (Unpublished).